Does an Indigenous Voice to Parliament Sound Like Equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples?

Following Australia’s 1967 Referendum, the Australian Constitution was amended to count Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the census and authorise the Australian Government to make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Every year, for more than a decade, Australia’s annual Closing the Gap reports have reiterated what many of us know: Successive Australian governments have bombed on hitting targets to close the gap of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander disadvantage in areas including health, education and employment.

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap, which came into effect on July 27 2020, is a revamp of the original Closing the Gap strategy [which began in 2008]. The Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations, and all Australian Governments, signed the agreement, in recognition that formal partnerships and shared decision-making between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is integral to overcoming the inequality experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The National Agreement is said to mark genuine partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations.

Australian voters to decide on Indigenous Voice to Parliament

Now, Australian voters are set to decide on broadening the agency of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to directly inform Government decision-making that affects their wellbeing outcomes, via constitutional reforms.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese recently proposed a draft referendum question on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament at the Garma Festival in northeast Arnhem Land.

In July, at the Northern Territory’s Garma Festival, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced that Australia would vote in a referendum on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. Essentially [very essentially], the Voice to Parliament is a body enshrined in the Constitution that would enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives to provide advice to the Parliament on policies and projects that impact the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. With a Voice to Parliament enshrined in the constitution, the Australian Government has a mechanism to make policies with the input of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, rather than for them.

Put like that, it sounds idyllic. Especially, when you reflect on the wasteland of impotent rhetoric, lapsed policy, doomed strategy, and archived reports that have all failed to achieve equality intended for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

A referendum process to encourage informed voting

Essential Research’s Essential Report is canvassing the sentiments of Australian voters early — maybe even before they really have them. Its August data indicates that 65 percent of its 1075 respondents support an alteration to the Constitution that establishes an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice — regardless of what these respondents have or haven’t heard about the Voice. But on that, some commentators sound positively itchy to fast-track Australian voters’ mind-making for them.

The referendum process shouldn’t be about shepherding Australian voters to vote “correctly” [“yes”]. It shouldn’t be about troubleshooting free thought. Or manufacturing a red carpet that leads to a fixed outcome. There should never be a right answer before the outcome. But there should be a right process for getting an answer [and many would say that answer is long overdue].

Imagine this. Invested voters are adequately informed to make a confident decision at referendum, and the referendum gets over the line on those terms. That sounds like an ideal outcome. That sounds like an outcome with democratic integrity.

If, like me, you already know that you intend to vote yes at this referendum, you might also feel shame and embarrassment that this referendum exists at this point in time [or at all] in the first place. All the same, the outcome will be all the better if the process is right-minded.

Many voices on the Voice

For the referendum to get the yes vote, there must be a majority vote at the national level, and amongst the States (four out of six). Only eight of the 44 referendums held in Australia have been voted yes.

There are guidelines that inform best practice for referendums but their value is to inform a successful referendum process, rather than engineer the “right” outcome.

Senator Pauline Hanson has already declared her commitment to opposing the Voice to Parliament, cranking out ‘Vote No’ merch, reportedly registering 46 web domains for web campaigning, and amplifying her view on social media and in the media. As reported in the Sydney Morning Herald, Senator Jacinta Price has voiced her opposition to the Voice, and labelled it “virtue signalling”. Liberal shadow spokespeople Tony Pasin, Phillip Thompson and Claire Chandler have all expressed concerns that the Voice function is too starved for detail.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton is still open to supporting the Voice, conditional on the detail the Albanese Government shares.

Former prime minister Malcom Turnbull, who opposed the idea in 2017, now says he will vote yes to establish an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

Irrespective of how you vote, there are a range of voices to agree or disagree with. And that diversity is alive and well amongst those who support the Voice, and those who oppose the Voice.

As Getting to ‘Yes’: Why Our Approach to Winning Referendums Needs a Rethink argues, we can all participate more faithfully in a referendum process when commentators switch the prevailing discourse from winning or losing the referendum, to running it to the best of our ability. As the paper states, the referendum process should be participatory, deliberative, inclusive, and fair.

One of the key stalling points in the current debate centres around how informed voters should be about the Voice before they vote at the referendum.

Prime Minister Albanese has expressed concerns that voters who are drawn too far into the weeds of the Voice model might dismiss it, based on any flaws, rather than embrace it on balance, based on its strengths. Others, meanwhile, argue that too little detail obstructs voters’ sight of what they’re voting for.

What some casual voters might not realise is that there is already volumes of information available about what form the Voice to Parliament might take.

Ex-prime minister Malcolm Turnbull has changed his view on the Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

The architects of the referendum should focus on communicating a proposal to Australian voters that is understandable and meaningful enough to enable them to make an informed vote. It needn’t be more, nor less.

Considering the Voice to Parliament on balance

Ex-prime minister Malcom Turnbull, who opposed the idea in 2017, is satisfied today that, on balance, the nation is better off approving the proposal, rather than rejecting it. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has recently adjusted his position, indicating that more detail on the Voice would be made known before the referendum.

The exact Voice design can be legislated after a successful referendum — as commonly happens in constitutional and political strategy — but that doesn’t mean Australian voters need to be in the dark, or under-informed, about what they are voting for.

For Australian voters who wonder what difference constitutional amendment might make, we can look at the impact the eight constitutional reforms that have previously passed have made.

Constitutional Referenda in Australia highlights that Australia’s 1967 vote to change the Australian Constitution to count Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the national census was slow to have a significant impact. But in time, it was seen to be essential to the process of change. Greater government spending was directed towards Aboriginal affairs, along with the possibility of overarching national legislation, such as the Native Title Act 1993.

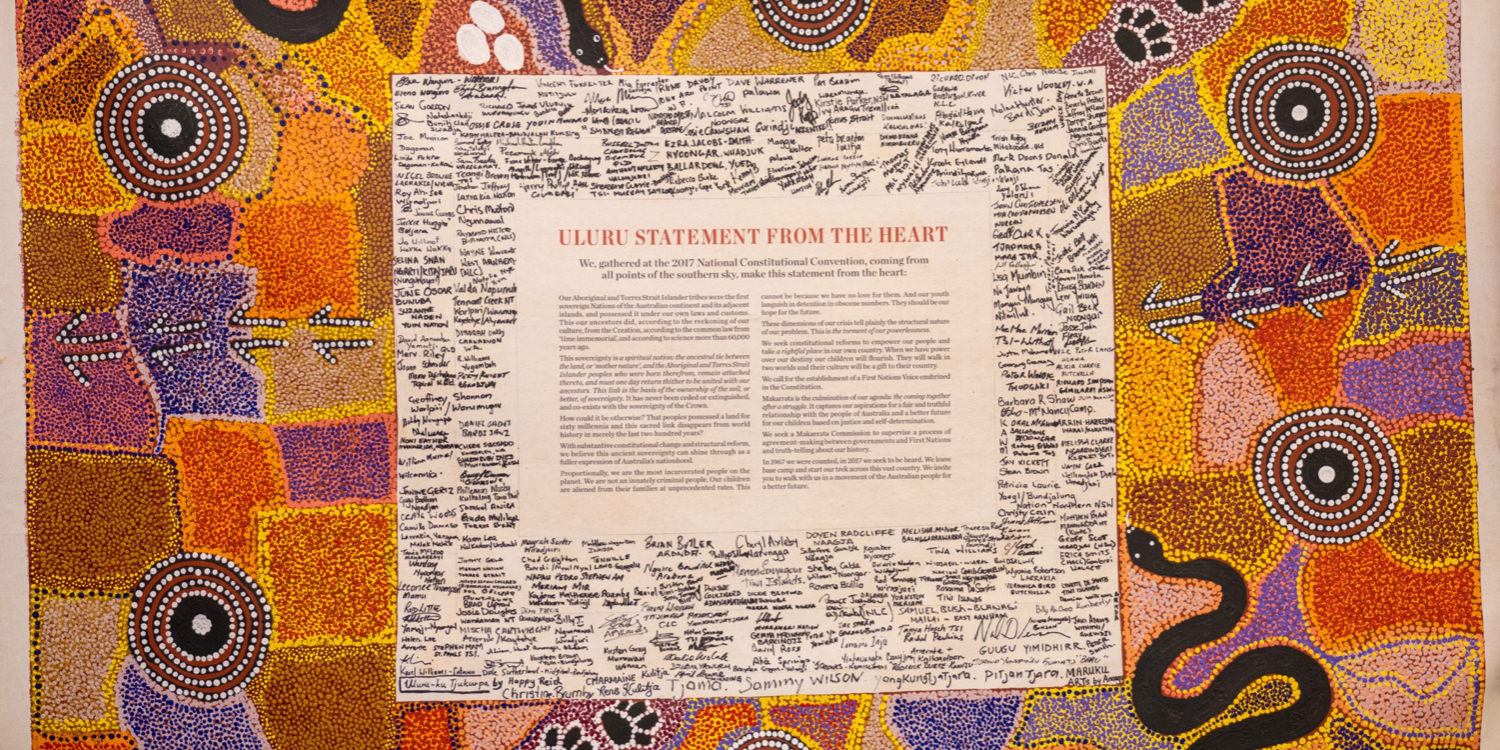

Professor Megan Davis, one of the architects of the Uluṟu Statement From the Heart.